What are healthy lung cells?

Normal cells in your lungs have very specific jobs and functions. For example, the cells in your lungs have a job—to move oxygen in and carbon dioxide out of your blood. The cells in your bloodstream have different responsibilities. Red blood cells carry oxygen throughout the body. The white blood cells fight infections. Healthy cells eventually stop growing and dividing when they get old. Injured cells can die.

What are lung cancer cells?

Lung cancer cells do not function the same way as healthy cells. They continue to divide and multiply, and do not die. Every cell contains genes, which are the “instructions” that tell the cell what to do. When genes are damaged or changed, they are called mutated. Some mutated genes in cells may cause cancer to develop.

Mutations can happen for several reasons. In families, a mutated gene can pass from parent to child. Others may have mutations due to exposure to cigarette smoke, radon, asbestos, or other things. Cells with these types of mutations are more likely to multiply in an abnormal way. This can result in a mass of cancer tissue called a tumor.

Symptoms of lung cancer can be similar to the side effects from various types of treatment. See our managing side effects chart here to learn more.

How can lung cancer cells spread?

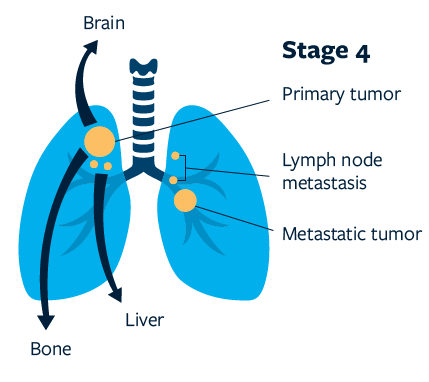

There are different ways that cancer cells can spread throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread through the bloodstream to other organs. Cancer cells can spread also through the lymph system by way of the lymph nodes. When the cancer cells travel outside of the lungs, they can form new tumors. The term used when cancer has spread is metastasize.

If lung cancer metastasizes, common sites are:

- brain

- bones

- liver

- adrenal glands (glands that release hormones)

Only cancers that begin in the lung are “lung cancer.”

If lung cancer spreads to another organ, such as the brain, it is still considered lung cancer. Lung cancer cells differ in how they behave. This makes them more likely to respond to lung cancer treatment, rather than breast cancer treatment, for example.

The most common symptoms of lung cancer are:

- A cough that does not get better, only worse

- Coughing up blood

- Chest pain that gets worse with deep breathing, coughing, or laughing

- Shortness of breath and wheezing

- Hoarseness

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

- Feeling tired or weak

- Infections such as bronchitis that does not get better, only worse

Types of lung cancer

The two main types of lung cancer are: small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The most common subtypes of NSCLC are:

- Adenocarcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Large cell carcinoma

The subtype of your lung cancer can be determined by a doctor called a pathologist, who looks at a sample of your tumor with a microscope. There are also other, less common subtypes of NSCLC.

If you have NSCLC, it is important to know your subtype so that your medical team can develop the right treatment plan for you. The majority of lung cancers (about eight out of ten) are NSCLC, and most cases of NSCLC (about five out of 10) are adenocarcinoma. Small cell lung cancers tend to grow and spread more rapidly and cause symptoms sooner than NSCLC. For these reasons, treatments for SCLC may differ from those for NSCLC (see here for more information on SCLC and NSCLC treatments).

What is the staging process?

After your diagnosis, your doctors will identify the type and stage of lung cancer you have. Staging cancer is a process where your doctors look at:

- tumor size

- location

- signs of spreading

Your doctor will need to run tests to determine the stage. The staging process will help your healthcare team develop your treatment plan and offer more information about your disease.

Questions and conversations are an important part of your care. For a list of suggested questions for your doctor, click here.

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

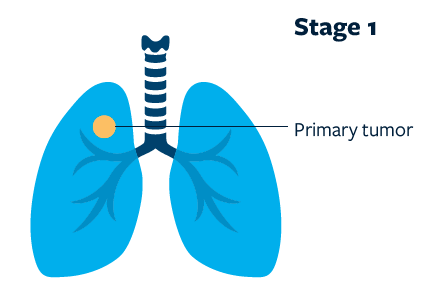

Stage 1

A tumor up to 5 cm wide that has not spread to any lymph nodes or other organs is classified as stage 1. These tumors are usually resectable (able to be removed surgically).

High-dose radiation therapy may also be used for these tumors (see this link for more information).

Stage 1A

- tumor 3 cm or smaller

Stage 1B

- tumor 3-5 cm wide in any direction

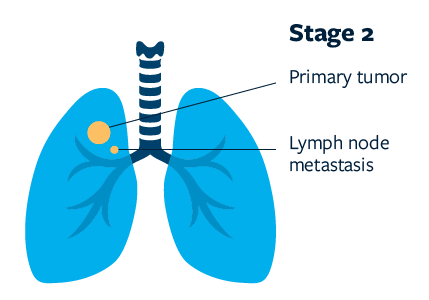

Stage 2

Stage 2 cancers may be a little larger than stage 1, and may have spread to lymph nodes on the same side of the chest (hilar lymph nodes), and/or may have begun to invade other structures within the chest. These tumors are usually resectable.

Stage 2A

- tumor 5-7 cm wide in any direction with no spread of cancer to lymph nodes OR

- less than 5 cm, but spread to lymph nodes on the same side of the chest

Stage 2B

- tumor 7 cm or wider in any direction with no spread of cancer to lymph nodes OR

- 5-7 cm wide, but spread to lymph nodes on the same side of the chest OR

- tumor beginning to invade structures within the chest OR

- more than one tumor in the same lobe of the lung

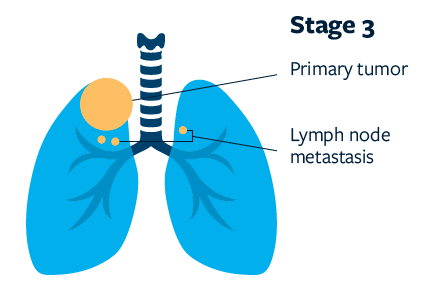

Stage 3

A tumor that has spread to the center of the chest (mediastinum) on the same side as the tumor OR has spread to lymph nodes on the other side of the chest, but does not appear to have spread to other organs outside the chest is classified as stage 3.

Often, stage III tumors are considered unresectable (unable to be removed surgically). Patients with stage 3 disease are assessed individually for resection, which may be performed after chemotherapy and/or radiation.

Stage 3A

- spread to lymph nodes in the center of the chest (mediastinal lymph nodes)

Stage 3B

- spread to lymph nodes on the opposite side of the chest or in the lymph nodes above the collarbone OR

- involves major structures, such as the heart

Stage 3C

- same as Stage 3B, but more than one tumor is

found AND/OR - the tumor has spread to other areas in the

chest cavity

Stage 4

Cancer accompanied by pleural effusion (a fluid buildup between the lungs and the chest wall that has cancer cells) or that has metastasized (spread) to other parts of the body is classified as stage 4.

Although stage 4 cancers are generally not curable, treatments may help you live longer and with an improved quality of life.

Refer to this link for detailed descriptions of treatments for each stage of cancer.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC)

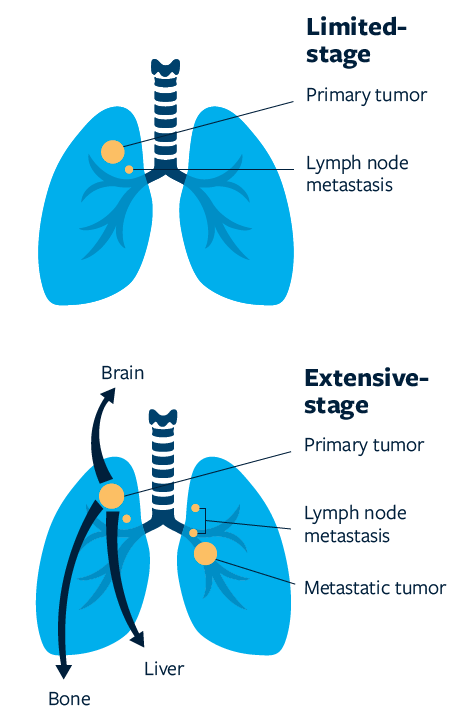

Limited-stage SCLC is cancer present in only one lung, which may have spread to surrounding lymph nodes. Treatment for limited-stage SCLC generally involves both chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Extensive-stage SCLC is cancer that has spread to both lungs, lymph nodes far from the original cancer, or other parts of the body. As with other advanced cancers, extensive-stage SCLC is generally not curable, but there are treatments available that may help you live better and longer.

Refer to this link for detailed descriptions of treatments for each stage of cancer.

What tests will my doctors do to find out the stage of my cancer?

Your doctors will determine the stage of your cancer by using any combination of several procedures:

- Computed tomography (CT) scans are sophisticated x-rays that show the body in crosssections. These cross-sections are very good at showing the location and size of tumors and enlarged lymph nodes. They may also identify bone lesions or other sites of disease.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scans can help determine where tumors are in the body. Because cancer cells grow faster than normal cells, they consume more sugar. A small amount of special dye that contains sugar is injected into a vein, and a PET machine is used to see where the sugar builds up, which identifies the location of cancer sites.

- Bronchoscopy is a procedure in which a doctor puts a small, flexible camera into the airway to look for tumors. The bronchoscope may have tools to remove a small sample (biopsy) of the tumor or lymph nodes for testing.

- Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) is a specialized type of bronchoscopy that uses sound waves to create an image of the tumor and nearby tissues to help the doctor find tumors or decide what area to biopsy.

- Navigational bronchoscopy uses CT scans and computer software to guide the physician to the target tissue. This form of bronchoscopy may be used when a tumor exists in the smallest parts of the airways, or to help doctors better find the right spot to take a standard biopsy.

- Bone scans create pictures of the bones. A special dye is injected into a vein, and a camera is used to see the dye. This tells doctors how healthy the bones are and whether they have any tumors in them. If you’ve recently had a PET scan, you likely will not need a bone scan.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses magnetic fields to produce detailed images of the body. MRI is particularly useful for finding abnormal growths in the brain.